La main droite de M. Hulot

Friday | June 5, 2009 open printable version

open printable version

Jacques Lagrange and Jacques Tati, with artworks by the former in the background

Kristin here–

David and I have occasionally mentioned the listserve of students and faculty, past and present, of the film studies area here at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Apart from job listings and inquiries for information about obscure films, the listserve offers a chance to discuss information and ideas-some of which have inspired blog entries for us.

Back in March, dissertator Charles Michael informed us that he had inherited a 1953 French painting by Jacques Lagrange (Les jardiniers, below). Seeking more information, he discovered that Lagrange had been a close friend and collaborator of Jacques Tati, working on all his films from Les Vacances de Monsieur Hulot onward. Naturally, as big Tati fans (the first essay I ever wrote for publication was on Les Vacances), we were intrigued.

Lagrange’s work with Tati

Lagrange (1917-1995) is best known as a painter and designer of tapestries, though he did a few theatrical sets. (The fullest online biographical sketch, in tortuous English, is available here.) He met Tati in 1947. The two hit it off, and they would spend afternoons or evenings bouncing ideas off each other. The film credits read “Avec la collaboration artistique de Jacques Lagrange,” a general phrase that reflects how the artist contributed at several stages of filmmaking. He worked on all the scripts as well as sketching settings and gags. He described their working method: “With Tati, the script usually started from a general idea. His second film grew out of the idea of a vacation, with the railway station, suitcases, trunks, trains. MON ONCLE is a more ‘social’ film. At Pecq, Alexandre Dumas’ villa has been carefully preserved, but in Saint-Germain, everything has been demolished. Like me, Tati favored the preservation of our heritage, as well as alluring modern buildings . . . . In writing a script, he started with sketches, not fully worked-out designs. Tati had trouble explaining what he wanted, so I had to interpret. I did thousands of sketches on restaurant napkins.”

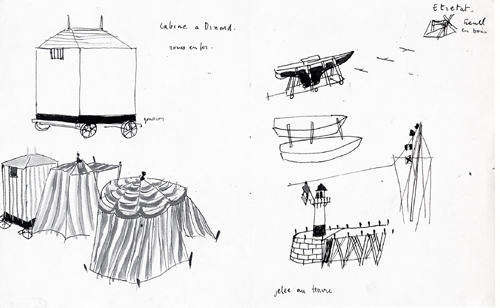

Here’s his drawing of the bathing cabines that lead to M. Hulot being mistaken for a peeping tom, as well as the boat being painted that slides into the sea. Whether it was made on a napkin, I don’t know, but I doubt it:

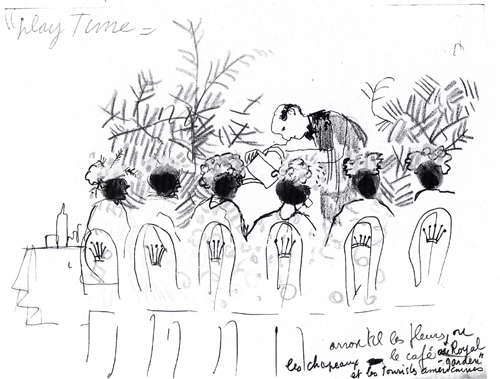

And the gag of the waiter “watering” the ladies’ hats in Play Time. At this early stage the idea was evidently that the waiter would use a watering can for the plants in the background. In the final gag, he appears to pour champagne onto the flowery hats (a funny framing that David illustrated here):

This sketch, by the way, provides pretty strong evidence supporting my claim that Tati intended the film’s title to be written as two separate words.

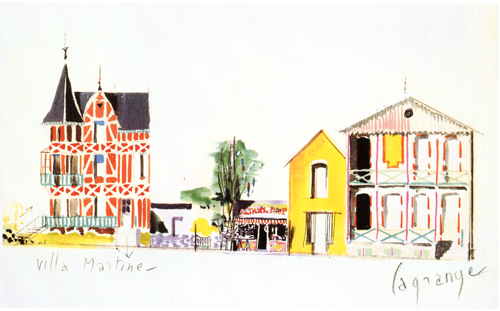

Lagrange went beyond such rough gag sketches. He also worked on the sets of Tati’s films, as this elegant painting for the “Hôtel de la Plage” and the guest-house where Martine stays in Les Vacances:

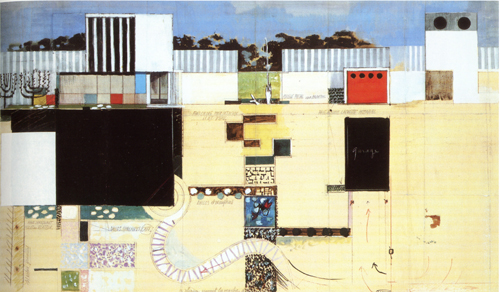

He designed the famous modern house in Mon oncle, including this combination bird’s-eye and profile view of the entire yard:

Tracking down Lagrange

Obviously Lagrange was a crucial collaborator of Tati’s, and yet he seems to be virtually unknown in the U.S. He has received more attention in Europe. In 2005, a slim coffee-table volume, Jacques Lagrange: Les couleurs de la vie: Peinture et tapisserie, by Robert Guinot, was published. It does not reproduce any of Lagrange’s work for Tati, but a four-page chronology (pp. 77-80) gives the best summary of Lagrange’s friendship and work with Tati that I have found.

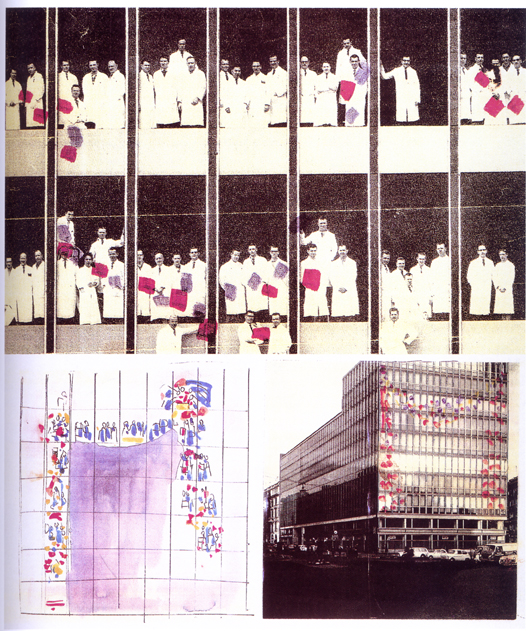

French books on Tati make reference to Lagrange. François Ede and Stephane Goudet’s book, Play Time (Cahiers du cinéma, 2002), quotes him on the construction of the film’s sets (p. 42) and includes some sketches for gags: the crown-topped chairs that leave impressions on the clothes and backs of those who sit in them (p. 57) and the scene of waiters carrying a placard shaped like a chef past diners who seem to be reminded of a corpse (p. 128). There’s also quite an intriguing graphic experiment with an unused gag for the film. Apparently somehow colored objects (folders?) held by people inside one of the glass-sided buildings would have formed a shape as seen from outside:

Marc Dondey’s Tati (Ramsey, 2002) reproduces some drawings for Les Vacances, including the beach scenes above, on pages 90-91, as well as the hat-watering sketch and the quotation above. (A book published in April under the same name, by the same author, but with a different cover is presumably a re-edition of this sumptuous volume; the number of pages is identical.)

Within the past several years there have been a few exhibitions devoted to Tati. One, La ville en Tatirama/La Città di Monsieur Hulot, was held at the University of Bologna. Devoted to three of Tati’s films, Les Vacances, Mon oncle, and Play Time, it produced a marvelous catalogue of the same name (Mazzotta, 2003) with a series of essays in French and Italian. This catalogue includes what may be the largest number of Lagrange’s Tati designs yet published, juxtaposing each with a selection of production photos from the relevant scene. The color painting of the Les Vacances buildings and the plan of the Mon oncle set are from this volume. Unfortunately the catalogue is now out of print and hard to find.

I say “perhaps” because I haven’t had a chance to see the catalogue for the Cinémathèque française’s current major exhibition, “Jacques Tati: Deux temps, trois mouvements,” running in Paris until August 8. David and I may get a chance to see it during our upcoming European travels. If so, we’ll report back. One Lagrange painting is visible in the photos on the Cinémathèque’s website, and no doubt there are other items by him as well.

(Books and exhibitions that include Lagrange’s work all credit the collection of Hyacinthe Moreau-Lalande, about whom I have been unable to find any information.)

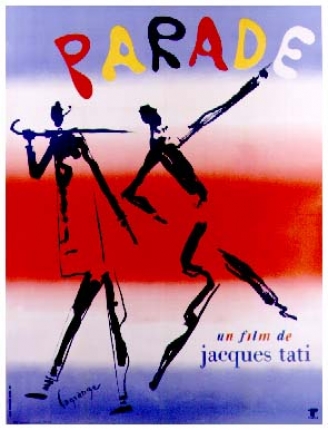

Despite the length of Lagrange’s collaboration with Tati, he designed a poster for only one of the films, the last one Tati completed:

A word on Pierre Étaix

As I was looking around at Amazon France for Lagrange material, I ran across a beautiful, fairly recent art book on the work of another Tati collaborator, Pierre Étaix. The book is Étaix dessine Tati (ACR Édition, 2007), by Francis Ramirez and Christian Rolot.

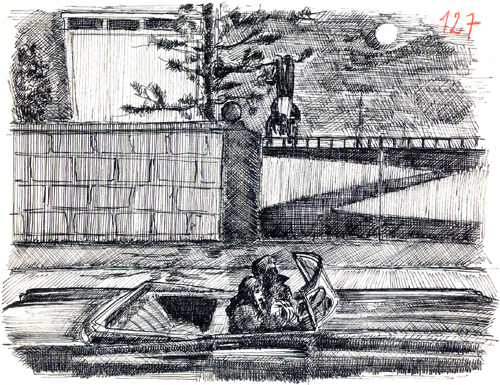

Étaix’s relationship with Tati’s differed considerably from Lagrange’s. It lasted only from 1954 to 1958, the period of the production of Mon oncle. An aspiring actor and filmmaker, Étaix was credited as an assistant director, though he also worked as a gagman. He produced thousands of drawings, collages, and paintings. Some, like those of Lagrange, were ideas for gags. This one involved Hulot getting himself into a fix where he is hanging upside down in a tree as two young lovers in a car pull up and stop underneath:

The gag ended up not being used, though Tati fans will recognize it as having appeared considerably later in Traffic. It’s amusing here to see it being played out by the gate of the Arpel household.

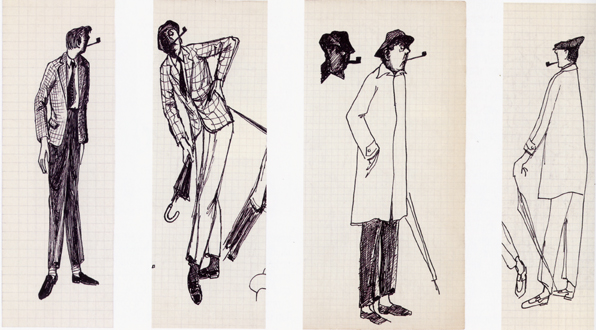

A fascinating set of drawings resulted from an assignment that Tati handed Étaix: to sketch visualizations of Hulot. Of course, M. Hulot had appeared in Les Vacances already, but only in his vacation clothing. His familiar short trenchcoat, umbrella, skull-fitting hat, and suede shoes hadn’t figured in that film. Only the pipe was already iconic of the character. Today it seems odd that there was some consideration of making Hulot distinctly more fashionable than he ended up being:

Tati’s influence is quite evident in the short films and the features that Étaix directed and starred in during the 1960s. He had some success with these, including an Oscar for his 1962 short, Happy Anniversary. He has continued to work as an actor, mostly in small roles (including in his friend Jerry Lewis’ still unreleased The Day the Clown Cried). Unfortunately legal problems have kept his 1960s films entirely out of circulation, as is explained on his official website.

David and I saw a couple of them in the early 1970s. I recall them as being charming comedies, definitely worth seeing. As of now, though, Étaix’s main presence on the screen is as one of Michel’s silent, sinister accomplices in Bresson’s Pickpocket.

The work of both Lagrange and Étaix reveals a great deal about Tati’s artistic methods. Perhaps the new burst of publishing that continues in the wake of the centenary of his birth (1907) will bring more such revelations.

Thanks to various Filmies: Charlie Michael, Colin Burnett, Tim Youngs, and Ben Brewster.